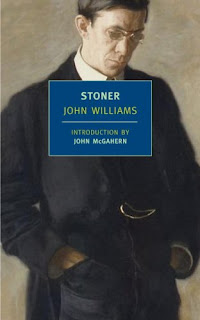

Stoner

By John Williams

NYRB Classics

This 1965 novel by John Williams (not to be confused with Steven Spielberg’s favourite hack composer)—although never a great commercial success in its own right—has been called a ‘perfect novel’ by The New York Times Book Review, and I couldn’t agree more. Stoner is, without any doubt, one of the best novels I’ve read in the last year, and may well become one of my favourite books, but part of what makes this Williams’s achievement so impressive is that he builds such an exceptional novel out of such unassuming material.

Stoner (no relation whatsoever to the more contemporary use of the term) is about the life of William Stoner, born to poor uneducated farmers in rural Missouri, and Williams even opens the novel by giving us a thumbnail sketch of his life story: ‘William Stoner entered the University of Missouri as a freshman in the year 1910, at the age of nineteen. Eight years later, during the height of World War I, he received his Doctor of Philosophy degree and accepted an instructorship at the same University, where he taught until his death in 1956. He did not rise above the rank of assistant professor, and few students remembered him with any sharpness after they had taken his courses.’

At this opening suggests, Stoner is not a particularly cheery novel, and its melancholy tone and choice of both an unassuming main character and setting may not seem immediately appealing. But Stoner works because of Williams’ precise and often scathing ability to map the emotion of his characters, whose very beings are often laid bare in a single sentence. One woman, for example, is described by noting that ‘Her voice was thin and high, and it held a note of hopelessness that gave a special value to every word she said.’ About another character, Williams writes that ‘Like many men who consider their success incomplete, he was extraordinarily vain and consumed with a sense of his own importance.’

This kind of approach to his characters recalls the wonderfully ambiguity of a book like Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and, like that novel, Stoner is able to enliven the quotidian until it is charged through with significance. Stoner’s often difficult relationships with his wife, his daughter and other members of his department all turn in unexpected ways that make them compelling. And as a character, Stoner, too, remains incredibly interesting despite his often bureaucratic occupation (indeed, I never would’ve thought that departmental meetings could be rendered as such tense and interesting moments in a novel—and I work as an academic!). While at points, his own inability to see the world around him can be maddening, his own bravery and determination at other points are impressive; Williams, himself, explains the paradox of Stoner: ‘He had, in odd ways, given [passion] to every moment of his life, and perhaps it was given most fully when he was unaware of his giving. It was a passion neither of the mind nor of the flesh; rather it was a force that comprehended them both, as if they were but a matter of love, its specific substance. To a woman or to a poem, it said simply: Look! I am alive.’

In a way, I’ve cheated a bit in this review; I haven’t said much about the plot, and I’ve quoted a good deal of Williams own writing, but that’s the case for two reasons: 1) I really, really, really don’t want to give away any details about this wonderful book and 2) Williams’s writing is the main attraction here. But to sum up, Stoner is a book about a man whose life is simultaneously both destroyed and enlivened by books—a point that the final moment of the novel underlines in what may be the book’s best passage. As it stands, Stoner is a monument to what the traditional, realist novel can still achieve; on the strength of this book, alone, Williams deserves to be known as one of the most interesting writers of the second half of the 20th Century. This is a book that would very much appeal to fans of Richard Yates (Stoner is similar in style and tone to Yates’s work), and it is an absolutely, indescribably phenomenal book; buy it now, read it and then read it again.

On a final note, it seems likely that John Williams is due for a bit of a revival; another one of his novels—a western entitled Butcher’s Crossing—will be adapted (by Joe Penhall, adapter of The Road) into a movie slated for release in 2013. Sam Mendes—who fittingly directed the film version of Yates’s Revolutionary Road—is apparently attached as the director. Regardless of the quality of the final movie, one can only hope that it will introduce more readers to this woefully overlooked author.

Recommended If You Like (R.I.Y.L.): Flaubert, Richard Yates and Beautifully Written, Depressing, Realist Novels

This review initially aired on Triple R Radio's Breakfaster's program.

This review initially aired on Triple R Radio's Breakfaster's program.

2 comments:

Thanks for your review of this book; it intrigued me enough to make me hunt down a copy. I've just read it and agree -- truly moving. I'm still trying to work out how Williams has weaved such magic with what is, at first glance, such ordinary subject matter. The only character I was less than satisfied with was Edith, who I thought lacked the light and shade possessed by others. Even so, I'm still in a space in which I can't quite bring myself to move onto any other book else because my thoughts keep returning to Stoner's world.

I'm glad to hear that you liked it, too; I had read the praise around it and approached it with scepticism, but really couldn't believe how good it was. I don't think I share your views on Edith, but I've also known many people in the U.S. who came from a sort of fallen, Southern pseudo-aristocracy, and who weren't so very far from Edith; perhaps she's too real for fiction...but one of the suggestions I liked in the book is that Stoner, himself, is at least partially responsible for what Edith becomes, so I think it's hard to make set and simple judgments about her, too. But I think you're absolutely right when you say this: "I'm still trying to work out how Williams has weaved such magic with what is, at first glance, such ordinary subject matter."

Post a Comment